Culturally Responsive Teaching

Archie Roach’s illustrated Took the Children Away is a great resource for introducing the history of the Stolen Generations with younger learners

In this final week of learning, the focus was on how to be a culturally responsive teacher in music education. Choosing which stories to tell, what narratives to focus on and how to ensure that the content of the class is reflective of the society in which it's being taught. This is no easy task, considering the diverse nature of classrooms and the differing influences from school and community on the values we should be espousing.

In looking at protest music, and comparing songs made in response to the Black Lives Matter movement both in the US and Australia, I found myself considering how social justice is represented through musical story telling. It made me reflect on how as teachers we have much influence in the narratives we present, and it's our moral duty to ensure that we aren’t simply conforming to the norm, and are actively empowering marginalised voices. When unit planning, is the repertoire in the classroom starting conversations, and is it asking students the right questions? What indeed are the right questions?

The NSW Department of Education says that teachers must adhere to strict guidelines on the presentation of ‘controversial materials’, and that the content “not be intended to advance the interest of any particular group, political or otherwise.” This to me seems limiting in the prism of music education, as so much music is inherently political, and the stories they tell are important to teach to students. As you might be able to tell, this has all left me with more questions than answers, as I find myself considering both the importance and implications of culturally responsive teaching.

Choral Pedagogy

Over the last 5 weeks of the Semester, I engaged in choral pedagogy masterclasses similar to the wind band ones from earlier. Again this was a space where I felt somewhat comfortable, having been in many choirs throughout school, professionally and in the community. Admittedly I have had very little experience conducting in front of a choir, and I quickly realised that the skillset needed to run an effective rehearsal differs in subtle yet noticeable ways to the concert band conducting I am more familiar with.

In trying to recall the great choral leaders and teachers I have had previously (not least of all Liz Scott) I at first attempted to emulate their teaching styles and infuse some of their warm up practices into my own conducting. I found this effective, but also came to acknowledge that leading a choir requires imparting your own personality and I would need to be vulnerable in order to be most effective. I discovered how much dedication is needed to truly understand the score, the different vocal lines and most importantly the musical expression that I wished to create.

These masterclasses not only helped with the development of my choral instruction skills, but also in building confidence in modelling strong singing, and even in some piano accompaniment (a skill that requires quite a bit more work…).

P.S. Shameless plug. I’m in the choir here with Nick Cave back in 2019, somewhere hidden in the back!

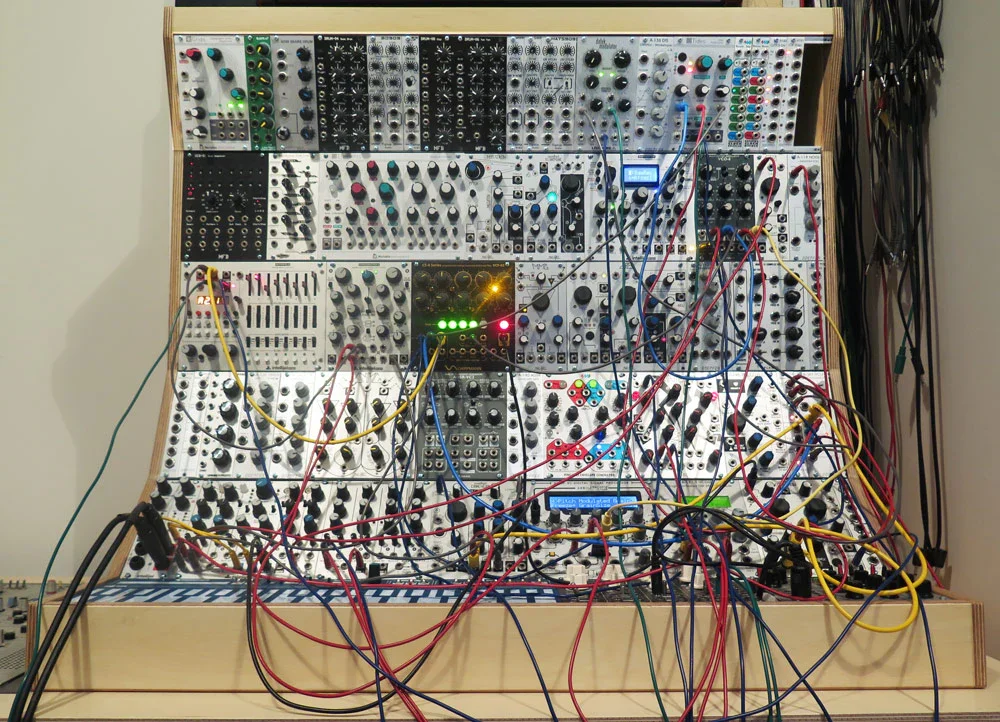

Musicking in Praxis

When I think of theory overload, I often relate it to the feeling of trying to make beautiful music from one of these terrifying modular synths!

The theoretical lens of Small’s “musicking” has affected my understanding of the motivations of music education, as has this week’s examination of the practical realities of preparing for the classroom.

Christopher Small’s argument that music is not an object but an activity has reframed how I think about participation in the music classroom. His idea is that the value of music lies in the relationships that are enacted through performing, listening, and collaborating. This ties into the idea of ensembles as social spaces, and of Lucy Green’s ideas of informal learning and of friendships being at the core of musical engagement. This tied in with our discussion about highly trained young solo musicians, and how their skills do not automatically translate into ensemble awareness or social development.

In contrast, the afternoon was spent grounded in inquiring into the lived realities of teaching and facing moments of ‘praxis shock’, where the theory doesn't always represent the situations we find ourselves in. Dissecting ideas like learning intentions, differentiation, and the importance of assessment in music reinforced to me the idea that effective musicking in schools requires thoughtful planning and attention to detail. My concerns were raised about the influences a mentor can have on early career teachers, and their capacity to have both positive and negative transformations in our outlooks. The realities of teaching seem to expand beyond the classroom and into interpersonal relationships, and it will serve me well to at least be aware of the political and social structures of schools.

Classroom Bullying and Moral Development

This week’s learning focused on bullying and adolescent moral development, and encouraged me to think more carefully about the broader ethical and relational responsibilities of music teachers.

The discussions around bullying were both illuminating and concerning. It seems inescapable that bullying of some form will appear both in the playground and in the classroom, and have the potential to cause students serious psychological harm. It is essential for teachers to be proactive rather than reactive in addressing instances of bullying, by understanding the social dynamics and modelling an inclusive and acceptive environment. I was reminded that bullying thrives when it goes unacknowledged, and that the music room must be a space where all students feel safe to participate.

In examining bullying we also looked at the moral landscape adolescents navigate, both in school and in the wider world, and the influence teachers inevitably have on their developing perspectives. Looking to the NSW Department of Education, they helpfully provide a list of core values of education, including ideas such as: Integrity, Excellence, Respect, Democracy. I thought about the responsibility I will have in teaching the intangible social and ethical skills embedded in music education, and how through my teaching practice I hope to be a strong role model for all students.

Side note: this week’s learning also left me with the insatiable earworm that is Sonny Rollin’s St Thomas. That song is going to be stuck in my head for some time still!

Listen to this awesome Japanese High School jazz band’s performance below, takes me back to my time in HS jazz….

Adolescent Behavior Theories and “Gifted” vs “Talented”

Mozart: the quintessional ‘child prodigy’

Our discussions this week were around practical behaviour strategies, with tips like maintaining lesson flow, using subtle non-verbal cues like eye contact or proximity, and reserving acts like removal from class to only when absolutely necessary. This led to exploring the concept of explicit teaching, and how it applies in music not only to instruction but also to behavioural expectations. To be successful in adapting adolescent behaviours to the classroom, teachers should clearly model how best to cooperate, build strong rehearsal habits, and to respectfully listen when others are performing.

In looking at McPherson and Williamon’s (2015) interpretation of Gagné’s Differentiated Model of Giftedness and Talent, I was intrigued in defining the distinction between the two. They argue that “giftedness” is the natural and innate abilities of a student, as well as their potential for excellence. “Talent” meanwhile is the application of this potential through practice and the development of technical skills. While giftedness arises from the appraisal of an early learner, talent grows through encouragement and from opportunities and relationships. This made me reflect on my own understanding of the terms, and how a teacher’s influence can help transform the potential of students into talented musicians. It also made me wary of prioritising those with a gifted label, and ensuring that my teaching practice remains egalitarian and for the musical development of all students.

Classroom Management for the Music Educator

Classroom management has now become a central part of how I’m shaping my identity as a music teacher, and nowhere was this more apparent than my experiences on placement! The NSW Department of Education notes that fewer than half of teachers feel well prepared for behaviour management when they leave university, and only 4 in 5 teachers feel able to control a disruptive classroom. Music classrooms are uniquely energetic, loud and sometimes chaotic spaces, which means clear rules and expectations become even more essential to a successful lesson.

I’ve learned that a strong classroom management plan isn’t necessarily about conceiving a strategy to control a class’s behaviour, but rather about creating a safe and predictable environment where students understand their expectations. In setting this up early, the aim is that positive reinforcement and calm responses to misbehaviour can make far more of a difference than anything reactive or punitive.

This leads me to the idea that the music room is a place where the “four Cs” of 21st Century learning naturally thrive. Critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity are all inherent in ensemble work, group performances and composition tasks. The successful ‘management ‘ of a music classroom therefore would be where students feel empowered to explore these skills with confidence and are engaged in deep learning. This has made me reflect on how I wish to encourage this learning through my own teaching. Jennifer Robinson’s idea of the “inspiring music teacher” resonated with me deeply, of someone who is reflective, connected, empowering, skilled, and grounded in care and social justice.

Credit: Becca’s Music Room

Pracitcum Reflections

My practicum placement was a rewarding and transformative experience that has strongly reinforced my desire to teach, while also exposing me to many of the challenges I will face in my early career. Going in with a desire to utilise my strengths in conducting and ensemble work, I often found myself working in a very different musical context, and was made keenly aware of the great diversity of the music teaching profession.

I found my school to have an incredibly robust music program, albeit one without a single orchestral instrument in sight. The students were however incredibly gifted guitarists, pianists, drummers and vocalists. To ensure I was able to respond effectively to their skillsets, my breaks often saw me frantically learning Ukulele chords in the staff room, or brushing up on my very limited guitar skills. There were moments however where I was able to play to my strengths, such as accompanying HSC performances and helping mentor senior students in their composition assignments.

Above: The music classrooms from my placement.

I experienced the full range of classroom behaviours across the 4 weeks, and had to adapt quickly to manage some of the most difficult situations. Much of my theoretical and behavioural understanding suddenly became irrelevant as I was faced with disengaged, confrontational and disruptive responses from students, and I felt my first true moments of ‘praxis shock’. While I recognised that many interactions were often down to my new introduction and to lack of familiarity with these students, it still brought into sharp focus how trust has to be built, and how routines and expectations that are established at the beginning of the year are so important to that success.

Being located in South Western Sydney, the school’s student population came from a great diversity of cultural backgrounds. I often found myself analysing the schools unit plans and curriculum implementation, and whether it was reflective of the students' lived experiences. I wondered if there might’ve been room to incorporate Arabic musical traditions reflective of a plurality of students' backgrounds, or indeed the musical traditions of any of the students. I was able to find relatability with the year 7 classes in particular through teaching the hit K Pop song ‘Golden’ on ukulele, and could see firsthand how their engagement instantly improved through their shared interest in the repertoire.

I found my confidence grew day after day, as I became more comfortable building relationships with students and establishing my authoritative teaching persona. Overall I found the experience to be richly rewarding in both seeing the musical and social developments of students, as well as of my own teaching practice.

The ukulele progression resource for ‘Golden’ I developed for the year 7 classes.

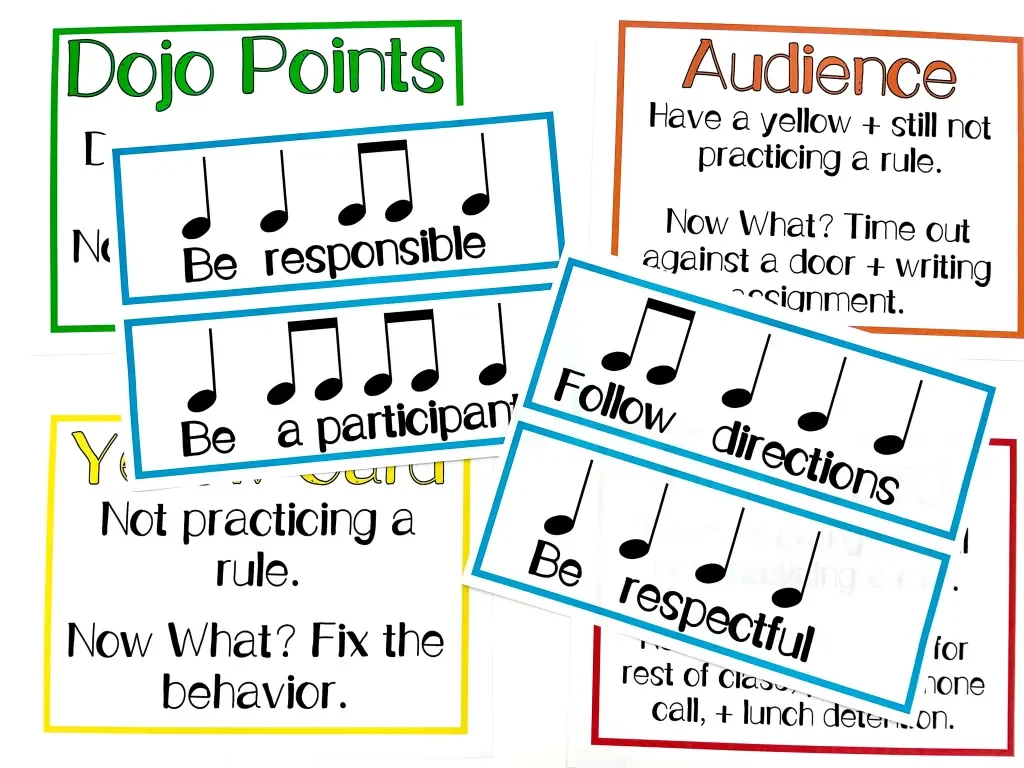

Peer Teaching Assessment and Placement Preparation

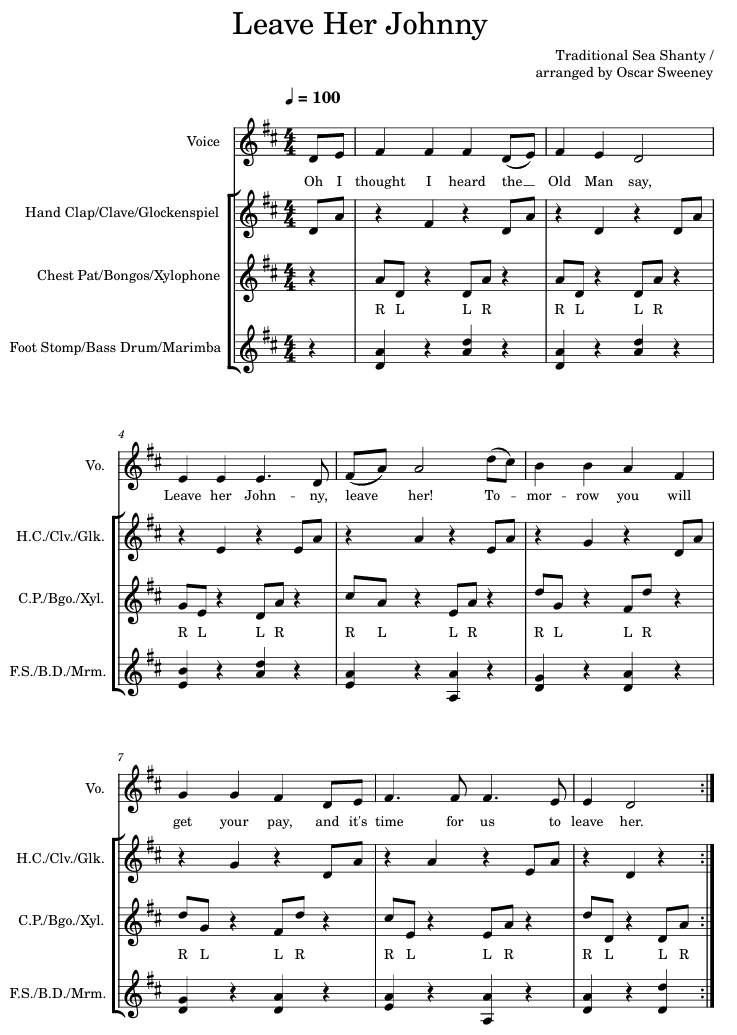

This week saw me working towards my assessment task of developing and delivering my own peer teaching lesson inspired by Kodály and Orff philosophies, as well as mentally preparing for my first placement experience the week after.

The song I chose to deliver in my lesson was a traditional sea shanty- Leave Her Johnny. I chose this song as its folk song origins allowed it to adapt well to being taught through Kodály/Orff methods, and the melody mostly follows the pentatonic scale (with a few additional passing tones) which allowed for Sofla integration. I found myself singing it all week to ensure I had the melody completely embodied! I found the delivery to be a success, in no small part because I had practiced the night before with my mostly ‘unmusical’ family.

In preparation for my placement, I did some reflecting on both the environment I would be stepping into, as well as what I wished to gain from the experience. All I knew was that the school was a public high school and in South West Sydney, and so I wondered if my experience in conducting and concert bands would prove to be useful, or if my skills in composition could come into play. I also pondered on the worry which most pre-service teachers have the most: how was I going to manage the behaviours in my classroom?

Listen to the rendition of Leave Her Johnny from the fabulous Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag soundtrack below:

And here is my score for Leave Her Johnny, which includes body percussion as well as non-pitched and pitched percussion adaptations to the rhythms.

Band Pedagogy

Above: a recreation of my struggles in learning the clarinet

The band pedagogy sessions across the first four weeks provided me further insight into the world of beginner band instruction. I already have experience in teaching in this area, currently conducting beginner concert band ensembles across primary and early high school settings, and so these sessions were invaluable in fine tuning my conducting and rehearsal skills.

Through these sessions I learnt the fundamental techniques of a new instrument to me, the clarinet, which required me to adopt the mindset of a beginner once again. This was a useful reminder of how cognitively and physically demanding the early stages of instrumental learning can be, and how quickly frustration can creep in. Sometimes from the perspective of teaching instrumental technique I myself learnt so long ago (in my case brass playing), there can be a disconnect from the challenges and struggles a beginner faces. This experience really brought home to me the necessity of clear modelling, and the true patience needed when working with novice musicians.

These sessions also strengthened my existing skills in conducting beginner concert bands, particularly in fine tuning my gestures and working on perfecting my legato beat patterns. Experiencing both the joys and challenges of instrumental learning again made me empathetic for the young players I conduct, and gave me a greater understanding of these students’ developmental needs.

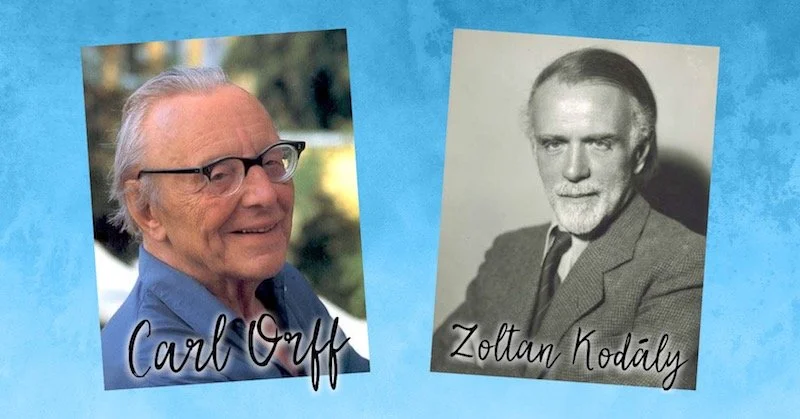

The Kodály and Orff Schulwerk Methods

Across the first four weeks of this Semester, I immersed myself within two of the most significant strands of music pedagogy: the Kodály method and the Orff Schulwerk approach. Much of this learning occurred through active music-making by singing, moving, clapping, improvising, playing instruments, and musical games. In this method of learning through making the music first, I began to see how these philosophies are built around the performing of music, and backgrounded and embedded the theory throughout the lessons. Experiencing these approaches from the perspective of a student allowed me to reflect on what elements of each philosophy I wish to implement in my own teaching, and how they will shape the educator I aim to be.

The Kodály approach was developed out of Hungary in the mid 20th Century and centres the voice as the primary instrument, as well as emphasises the importance of developmental sequencing and inner hearing. In these classes I learnt and sang folk song repertoire, practiced implementing solfa hand signals and participated in structured singing activities and ensemble games. I found this clearly scaffolded method of instruction made the learning process accessible and always engaging. Occasionally the material we were learning became quite complex in body and rhythmic coordination, and I experienced first-hand moving beyond Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development and into frustration. I was often surprised by how effectively the simple musical material could quickly lead to exploring complex concepts, and contribute to the development of ‘whole musicianship’. This is explained by Kodály as the four elements of becoming a well trained musician: a well trained heart, mind, ear and hand, that are all working in equilibrium. These ideas align with McPherson's ideas of the multi-modalities of being a musician, which requires developing every facet of musicianship, including less obvious ones such as appraising, analysing, conducting and even teaching itself.

The Orff Schulwerk approach is a complementary pedagogical method, and I found its focus on embodied learning to work well in tandem with the Kodály method. Its emphasis on combining music and movement, as well as incorporating body percussion, ostinato and layered ensemble part work helped to create a strong sense of collaboration in the classroom. This approach made me reflect on the often dominance of the Western art music tradition, and how its separation of music and movement is anomalous to the vast majority of musical traditions worldwide where the two are inseparable. I found that approaching musical concepts in this kinesthetic way also made them immediately tangible, and how teaching through these methods can help support diverse learners who may rely more on movement to understand rhythm and develop a sense of beat.

Working and learning within the Kodály and Orff methods really highlighted to me how essential it is to have confident vocal modelling, and the role of the teacher as facilitator in establishing a supportive learning environment. I found that moving beyond simple direct instruction and teaching as part of the collective provided a way in for all types of learners, and ensures that every student has an opportunity to be actively engaged at all times.

When I reflect on these pedagogical philosophies together, I can see how each contributes distinctively to my emerging professional identity. Kodály offered a framework for building musical literacy through a clear structure, as well as providing musical systems such as solfa and ta-ti-ti. Orff meanwhile emphasised musical embodiment, and allows for inclusive engagement through kinesthetic learning. Experiencing both of these approaches practically broadened my understanding of the variety of pedagogical methods, and opened up my worldview to engaging with different methods of learning.

Below are some explainer videos of both Kodály and Orff Schulwerk.